“…unless this story is written now, I know I shall never have the courage to tell the truth about the matter—not from fear of ridicule, but because I myself shall soon cease to credit what I now know to be true.”

Robert W. Chambers, “The Harbor-Master”

“‘The Harbor Master‘ gave me quite a wallop in 1926, when I read it…”

—H.P. Lovecraft to J. Vernon Shea, January 28, 1933

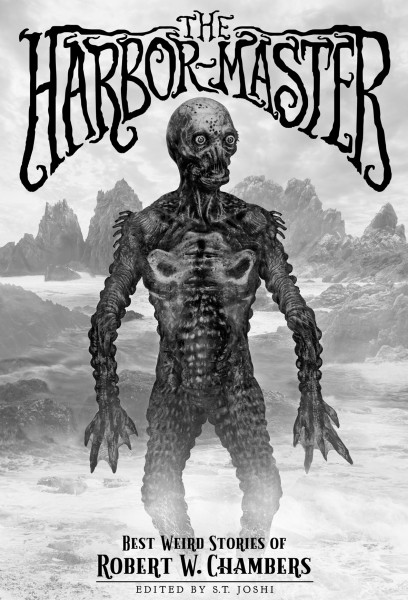

Robert W. Chambers’ is one of the most commonly cited author names among Lovecraft fans. His “King in Yellow/Yellow Sign” mythos has spawned almost as many stories from writers through the decades as Great Cthulhu and the Old Gent himself. In quite few cases, I like the contemporary stories it has birthed more than the original material. Prior to his untimely death, Joe Pulver Sr. was one of our greatest practitioners of the Yellow Mythos tale, and his love for this work was infectious. But Chambers wrote a lot of other work (indeed, he made his money writing romances) and I want to call some attention to it, and one story in particular. Hippocampus Press has recently released a paperback called THE HARBOR-MASTER: BEST WEIRD STORIES OF ROBERT W. CHAMBERS, and as always, I’m grateful to them for sending me a copy. The title story of this collection (part of their Classics of Gothic Horror book series) was one that, as you can see from the quote above, made quite an impact on H.P. The cover image alone (Aeron Alfrey) is enough to draw comparisons to Lovecraft’s own “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” or the Universal picture, CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON (though the inspiration for that monster apparently was the Oscar statuette!). Tonight, I want to see just how much of an influence it might actually have been on Lovecraft.

Our tale follows the adventures of a young zoologist following up on a claim that a man named Halyard in the fictional town (region?) of Port-of-Waves, New York has a male and female pair of Great Auks. The Great Auk was a bird like a giant penguin that went extinct around 1850, but this person claimed to have a pair and was willing to sell them to the Zoological Society for the paltry sum of $10,000 (this story was published in 1899, so that was quite a handsome sum). Obviously, were it true, such a find would be momentous, but our zoologist isn’t hopeful. “No man in his senses would keep two such precious prizes in a pen in his backyard…and I was perfectly prepared to find anything from a puffin to a penguin in that pen.” As his boat was pulling up to the harbor, he noticed something strange atop the rocks, but chalked it up to being an otter and moved on without a second thought. He met Halyard, a detestable man, who was cared for by an attractive young nurse. Halyard stunned him by actually having the pair of auks, and to his greater surprise, they had hatched young! After much awkward social interaction over the course of a few days in a neat take on a gothic locale, the auks were packed up and readied to ship back to the Bronx. Interspersed in those awkward conversations was mention of an amphibious humanoid they called “the harbor-master” but our protagonist dismissed it as nonsense.

The story is actually very predictable and you can tell from what I’ve already written where it ends up. One should not be so quick to dismiss tales of amphibious humanoids! The real question is, just how much of an influence on HPL, and particularly, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” was this present story? I’d hazard quite a significant one, actually. Published well before Lovecraft wrote “Shadow” (1931), he commented several times to correspondents about this tale as early as 1930. In a letter to Frank Belknap Long in 1930 he simply wrote, “God! The Harbor Master!!!” There’s a number of elements in this story that make their way into “Shadow” one way or another: the amphibious people who breathe through gills, an outsider traveling to place he doesn’t belong, a swooning hero, hints of xenophobic or racist explanations for the strangeness, and even the style of the opening.

It’s fun to note, too, what doesn’t influence him. There’s a romantic sub-plot going on in “The Harbor-Master” that HPL doesn’t pick up, romance not being his strong suit. Chambers, though, worked romance into many of his weird fiction stories. Another thing Chambers did well here was include humor. There were two places where I laughed out loud, including this gem of an exchange at dinner: “As for Halyard, he was unspeakable, bundled up in his snuffy shawls, and making uncouth noises over his gruel…”Yah!” he snapped, “I’m sick of this cursed soup—and I’ll trouble you to fill my glass—”

“It is dangerous for you to touch claret,” said the pretty nurse.

“I may as well die at dinner as anywhere,” he observed.

“Certainly,” said I, cheerfully passing the decanter, but he did not appear overpleased with the attention.”

The writing, as you can see, is also a lot of fun. It’s clean, crisp, and descriptive without the florid language Lovecraft would come to be known for. It’s possessed of an old style that makes me know immediately I’m reading something comfortably from the past. If I’m honest, it’s a style that warms me. But it is not unapproachable, as I thing some of his “King in Yellow” stories can be (“The Repairer of Reputations;” “The Yellow Sign,” for example). I found this very easy to read.

I had a lot of fun reading “The Harbor-Master” and really enjoyed getting some Chambers under my belt besides the Yellow Mythos stuff. I’d be very intrigued to know if the great auks here influenced HPL when he was writing “At the Mountains of Madness,” but I have no way of telling that. If you’re at all interested in the Yellow Mythos stories, or Chambers other weird fiction, this would be a book to pick up. It’s got eleven other stories in it besides this one, including the big Yellow Mythos tales. For my next review, I’ll be doing a story from the volume released alongside this one, UNDER TWIN SUNS: ALTERNATE HISTORIES OF THE YELLOW SIGN edited by James Chambers (no relation) and we’ll get a full dose of Yellow Mythos then, so if that’s what you came here for, stay tuned.

Until next time, I remain yours in the Black Litany of Nub and Yeg,

~The Bibliothecar